- Home

- Jana Bommersbach

Funeral Hotdish

Funeral Hotdish Read online

Funeral Hotdish

Jana Bommersbach

www.JanaBommersbach.com

Poisoned Pen Press

Copyright

Copyright © 2016 by Jana Bommersbach

First E-book Edition 2016

ISBN: 9781464204593 ebook

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in, or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

The historical characters and events portrayed in this book are inventions of the author or used fictitiously.

Poisoned Pen Press

6962 E. First Ave., Ste. 103

Scottsdale, AZ 85251

www.poisonedpenpress.com

[email protected]

Contents

Funeral Hotdish

Copyright

Contents

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Author’s Note

Endnotes

Bibliography

More from this Author

Contact Us

Dedication

This book is dedicated to my

North Dakota roots and my family lines:

Peterschick, Bommersbach, Schlener, Portner.

Chapter One

Friday, October 15, 1999

“I AM SO, SO, SO, SO, SO, SO HAPPY!”

Amber Schlener never felt this fantastic in all her seventeen years. Even her terrible thirst didn’t matter.

She wasn’t just happy, she was ecstatic. Every pore in her body vibrated life. Every cell tingled with joy. She was thrilled and powerful. On her best days on the basketball court, she’d never had this much energy—this euphoria—that would keep her dancing forever and never get tired.

Her feet bounced like a marionette, on and off the floor of the old hayloft. She sprang up, the wood boards giving slightly under the pressure of all the dancers, but that was a good thing. Amber laughed out loud, surprised that she could dance with such abandon and such rhythm. Her arms flailed around her, doing their own interpretive dance. She watched them as if they belonged to someone else.

Suddenly, her nose demanded all her attention and she inhaled deeply the musty, moldy smell that would forever be embedded in these eighty-year-old walls. In its day, the scent had been the sweet smell of alfalfa bales that fed generations of Holsteins, but the odor changed as the hay dried out and sat stashed away. Amber couldn’t think of a farm without the smell of alfalfa, and in a flash of brilliance, she decided that if North Dakota ever added a state smell to its list of icons, it would be alfalfa. She had to remember to tell Johnny and he would agree.

Then she realized something incredible. The knee she’d wrenched in last week’s game didn’t hurt. “My knee doesn’t hurt—IT DOESN’T HURT”—she kept yelling at Johnny, like it was the most miraculous truth in the world. Quickly she discovered her bad tooth—facing a dental appointment on Monday—didn’t ache. “My tooth doesn’t ache,” she repeated to her boyfriend, louder with every telling.

“See, I told you it would be great,” Johnny yelled into her ear. “Nothing to worry about.” She grinned in agreement. Her hesitation had been foolish. Most of her classmates had agreed to try it. She was one of the last holdouts, but now she was so glad they’d convinced her.

Amber swirled and jumped and swayed and leaped to the ear-splitting music from Lonnie’s turntable. He kept playing “The Devil Went Down to Georgia” by Charlie Daniels, interspersed with Bruce Springsteen’s Dancing in the Dark. He’d tried to slip in Shania Twain’s “That Don’t Impress Me Much,” but the ballad was too slow for the frantic dancers. Cher’s “Believe” worked once, but these seventy-eight dancers wanted the hot fiddle or the driving guitar, so Charlie and Bruce were the headliners tonight.

Amber reveled in her pain-free, fantastically fabulous body. She loved the way her skirt swirled around her, twisting even more so it created its own unique dance. Oh, if Aunt Gertie could see her now. She’d admire how the dress they’d sewn together was flowing like a fancy dress in a television ad. Amber couldn’t pull her eyes off her skirt. Who could guess that a piece of floral fabric, hemmed last night, could move so beautifully?

“Look Gertie, look,” she screamed while she twirled, as though her elderly great-aunt, safe at home—probably already in her nightgown—could see this marvelous skirt now. When she held the skirt out like she was doing a curtsy, she couldn’t believe how soft it was. She rubbed the fabric between her fingers and wondered why she’d never realized its luxurious feel in all the time it took to cut out the pattern and sew the pieces together. This was the softest dress ever. She decided right then that she would wear this dress every day of her life.

“Feel it, Johnny, feel it,” she hollered, but he was now in his own world, his arms wrapped around himself like he was discovering the strength of his massive shoulders.

Amber laughed again, more giggle than laugh, and now saw for the first time that she didn’t only feel fantastic and happy and pain-free—better yet, she felt no fear. Of anything. She didn’t fear her mother’s scorn for Johnny. She didn’t fear failing geometry. She didn’t fear getting fat. She didn’t fear what waited for her out there after graduation. She didn’t even fear Johnny’s creepy uncle, Leroy Roth and his Posse Comitatus rants.

“So this is how it feels not to be afraid of anything,” she cried out loud, to nobody in particular, but to reaffirm to herself that this sensation was indeed possible. Until that moment, she wouldn’t have believed it.

To think, she marveled, one little yellow pill could do all this!

The class valedictorian—not yet official, but everyone knew—bumped into her and started apologizing like he’d committed a crime.

“Roger, it’s alright,” Amber crooned, and reached out to hug him. He couldn’t believe his luck. He never dreamed Amber Schlener would ever hug him. He hugged back like he was hanging onto a life raft. Then he watched her turn and hug Marilyn, and then Carolyn and then Jack. Some kid from another town came by and she hugged him, too. Roger didn’t care that she was hugging everyone. He didn’t care why she was being so generous with her affections. He just cared that she’d hugged him. He would remember the feeling even when he was an old man.

Johnny watched all this, not with jealousy and concern, but with glee. Amber was so happy, which made him happier than ever. He shed any concerns he had about talking her into this. He grew more powerful and sure and strong and joyful. He reached out and one-arm hugged his best friend around the neck, pointed his head at Amber, and shouted “Kenny, look at that!”

Kenny Franken threw back his head and bellowed—his own rapture so overwhelming, he t

hought he would burst. He shouted back, “They don’t call it the Hug Drug for nothing!”

Steve stumbled into them as he missed a step in his version of dancing, and sang out the mantra he’d been repeating all night. “Wunnerful, wunnerful!” Johnny and Kenny found it a hoot that the ghost of Lawrence Welk should be visited on this dance—as far from “champagne music” as one could get—and egged Steve on. “Wunnerful, wunnerful,” he screamed as he staggered away into a crowd that knew little about the state’s favorite son except that famous phrase.

Amber was trying to tell someone something profound, but her voice was hoarse and raspy. She yelled at Johnny that she needed some water as she made a beeline to the orange Igloo against the barn wall. Used plastic glasses were scattered around the plank table. She picked up one and flung out the remains of the last drinker to fill it for herself. Even though it was warm, this was the best water she’d ever tasted. Amber thought she could drink this entire Igloo dry if they let her, and maybe if she did, she could get rid of this thirst. Johnny joined her and didn’t even bother with a glass. He picked up the Igloo and tilted it to let it flow into his mouth in a steady stream. Amber roared and their classmates chanted, “Johnny, Johnny, Johnny,” as he drank until he choked.

At that moment, Amber was as happy as any human being on the planet. She was the luckiest girl in all of North Dakota. What was the date? She wanted to remember because this was a date she’d put in her diary.

Friday, October 15, 1999.

She wasn’t the only one who’d always want to remember when the Class of 2000 gathered to dance the night away in the Jacobsons’ old hay loft.

It was supposed to be a party just for them, but word had gotten out—underclassmen from her school had come, so did kids from towns nearby, and if she’d have been paying attention, she would have realized it was almost impossible to squeeze any more up the narrow wooden steps that led to this loft. The more the merrier, Johnny said early in the evening. Amber adopted his invitation.

Someone offered her a bottle of Royal Crown, and a small sip burned so much she wished she hadn’t. She handed the bottle back with a smile and yelled in the stranger’s ear, “I’m not a drinker.”

He smiled back at her and winked, “No baby, you’re doin’ alright all on your own.” She saw Johnny swigging from someone else’s bottle and it didn’t even cross her mind that he might be getting too drunk to drive.

And then, like switching a channel, Amber thought of all the wonderful things ahead.

In seven months, she’d put on the rose-colored robe and miter hat with its gold tassel and walk down the aisle of the Northville Public High School. Her class of thirty-two would appear in alphabetical order, Amber marching in right behind Johnny. Everyone she loved would be in that high school gym—her mom, her surviving grandparents, her aunts and uncles, cousins, friends, and of course, Johnny.

“He’s not only my first love, he’s going to be my only love,” she’d confided to Aunt Gertie, who she counted on to help sew her wedding dress someday.

Between now and graduation, there was nothing but excitement. Thanksgiving, Christmas, the Millennium—the world’s not going to end, she knew now with certainty—the senior class trip, hopefully a basketball championship, the graduates’ luncheon at that beautiful Victorian mansion on Lake Elsie, the senior play, finishing the yearbook, prom—oh, PROM, she and Maxine were already pattern shopping for their dresses—baccalaureate, the graduation ceremony, the family dinner after.

And then, with the scholarships that were sure to come through, off to UND and a teaching degree. Third grade, Amber thought. She wanted to teach third grade. She had little cousins that age and enjoyed them most—the younger ones were too whiny and the older ones too snotty, but a third-grader was a loving, wondrous child and she could already see coming home to Northville to teach third grade in the very school she’d attended all her life. She’d live on the farm with Johnny and drive the three miles into town each morning and eventually, they’d have their own children attending school right here in this safe little town that she loved.

Her best friend had the opposite dream and Amber couldn’t imagine going off to the Twin Cities to live with strangers and not have family around. But that’s what Maxine wanted, and so Amber had promised to visit her in Minneapolis whenever she could. With teaching third grade and raising a family and farming…Amber already worried their friendship wouldn’t last and had doodled in her notebook, “Never lose Maxine.” But now, as she danced atop this glorious night, she no longer had that worry.

Amber Schlener had no worries at all. Her dreams would all come true and the life ahead would be filled with love and delight. She was certain. More confident than she’d ever been. She laughed at herself that she’d been such a scaredy cat lately, fretting over every little thing and not having faith in herself. But that had disappeared. What a glorious feeling to put that behind her and face the world with this strength. If anyone had told her she was going to be president of the United States someday, she’d have believed it.

“Maxine, we’ll be friends forever,” she shouted to the blond cheerleader who was dancing a few feet away. Maxine couldn’t hear her over the blaring music, but moved toward her, drawn by Amber’s glorious smile. Whatever her precious friend was yelling had to be something good and Maxine wanted to hear.

The best friends were beaming at each other—laughing and kicking up their heels on the brink of their new lives—when things started to go black in Amber’s head.

She blinked several times to clear her sight, but instead of seeing Maxine and her classmates all around her, she saw a slide show of images against a black background.

Johnny on his Dad’s combine. Mom drying dishes. Aunt Gertie in her garden. A basketball net. Her father’s gravestone. A sewing machine. Her scuffed tennis shoes. Father Singer giving out communion. The snowball bush at her grandma’s old house. “We Love Our Buccaneers” poster in the bakery window. The Nun scarecrow. Her 4-H blue ribbon. The whirly balloon at the Dairy Dell. Playing Dorothy in the children’s summer theater. Baskets of flowers on Main Street. The Wild Rice River sign on the Interstate. Mom teaching her to dance. Mr. Carlblom in geometry class. The Delaware State Quarter. Writing Mrs. Johnny Roth, Mrs. Johnny Roth, Mrs. Johnny Roth. Buying makeup with Maxine. The stained glass window in church. The bride doll on her bed. Flinging a three-pointer. Washing her long brown hair. Kissing Johnny.

And then the images came in so fast, she couldn’t make them out from the blur. Now and then, she’d think she recognized something—“was that…was that…was that…?” But it shot by so rapidly she wasn’t sure and in the time it took to consider it, a hundred other images had already raced past her eyes.

Amber didn’t feel herself fall.

She couldn’t hear Maxine screaming her name.

She never knew Johnny was already unconscious nearby.

The slide show stopped.

One ending frame.

The last thing Amber Schlener ever saw was the father she knew only from his picture.

He was smiling at her.

Chapter Two

Friday, October 15, 1999

Like all journalists, Joya Bonner didn’t want to admit her scoops were often due to dumb luck. Skill. Smarts. Intuition. Observation. Cleverness. She’d opt to all of these. But she preferred no one ever knew dumb luck led her list.

Still, plain old dumb luck got her the Sammy the Bull scoop. If she’d been honest with the audiences that asked, “How did you break the sensational story about Sammy’s dirty Arizona connection?” she would have answered, “I was interviewing a student in the Goldbar Coffeehouse in Tempe when a character like actor Joe Pesci walked in.”

Short, strutting, black leather jacket over a white tee-shirt, dark hair slicked back with a grease Joya didn’t know was available these days, the guy looked like a Central Casting Mafia hi

tman. She wasn’t the only one who saw the resemblance—the piano player pounded out the first few bars of the theme song from The Godfather. The strutting man beamed and waved at the tribute.

Joya chuckled to herself and wondered who he was, but decided that you see the strangest types on a university campus. Probably a history professor. Or poli sci.

She turned back to her interview with an earnest graduate assistant blowing the whistle on research fraud. Millions of dollars were at stake. The reputation of Arizona State University was on the line. This was a really big story.

The explanation was complicated and compelling. Joya riveted her attention on the young woman who promised she had documents to prove everything she was saying. Joya listened attentively—one of her best traits, one that came from years of listening to relatives visit back home in Northville, North Dakota. She’d learned there that if you listened, folks would tell you almost anything. It was a major secret of her success.

Her focus would have stayed on research fraud, except the girl left for the bathroom. While Joya waited, she scanned the room to catch the Pesci impersonator holding court in a corner, surrounded by students. She couldn’t hear what he was saying, but she could tell he was pontificating. He’s sure full of himself, she thought. A student handed him a paperback, and the guy signed it with a flourish. Then she heard the most astonishing thing. A pretty coed in a Sun Devils tee-shirt and jeans without knees interrupted, yelling, “Mr. Bull, Mr. Bull.”

The other students tittered, the girl looked flummoxed, and “Mr. Bull” smiled like a streetwise bad-ass.

The girl was so excited she yelled her question so Joya could easily hear. “You didn’t really kill nineteen people, did you?”

Joya Bonner stopped breathing as skill-smarts-intuition-observation-cleverness met dumb luck.

It couldn’t be, she first thought. Nah. Impossible. Or is that why the guy looks familiar? Is that why he resembles a Mafia character? If that guy in the corner really is that guy, then what the hell is Sammy “the Bull” Gravano doing in Arizona?

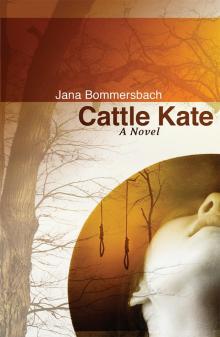

Cattle Kate

Cattle Kate Funeral Hotdish

Funeral Hotdish