- Home

- Jana Bommersbach

Funeral Hotdish Page 11

Funeral Hotdish Read online

Page 11

And then Nettie stopped talking and started crying and everyone guessed she’d come back to the present. But they were wrong. Nettie had gone to the spot in her heart that had been the darkest until now—the spot she’d never reveal to anyone. The spot she would deny was even there.

Two nights after the shower, Nettie and Richard had a fight, a stupid quarrel about the baby’s name.

She and Richard normally saw eye to eye on everything. They had since they’d started dating in their sophomore year. She was strong-willed, like him (and he loved her for it) and normally they worked everything out by talking it through. But Nettie’s hormones were playing havoc with her emotions and she would decide the name of their first child.

If a boy, she wanted him named after her father. If a girl, after her mother. That meant Amos or Eunice.

Richard laughed out loud, convinced his wife was joking. She started to cry when she realized he thought the names were ridiculous.

“Those are fine names, fine names,” he cooed to quiet her down. “But not for our child. Those are old people names. You want to honor your parents, but do you really want our boy called Amos? Or our girl called Eunice? Think of the horrible nicknames they’ll get. Ammo. Mousey. Unnie. Ewie. God, we can’t saddle the kid with that!”

He was sure she’d see his wisdom, and offered his own personal selections, Joshua if a boy, Amber if a girl.

“What’s so special about those names?” she spat back at him. “What, is Amber an old girlfriend’s name? It sure isn’t your mom’s. And Joshua. When did you get cozy with biblical names?”

If Richard Schlener had had more experience with hormonal pregnant women, he’d have realized this was a momentary fixation that would pass, like her taste for sour pickles. But he was as new to this as she was, and she wouldn’t stop crying and wouldn’t stop insisting her child was going to carry her parent’s name and if he didn’t like it, he could go to hell.

“Oh, so if we’re thinking of parents’ names, it’s only your parents? What about mine?” he asked in anger. “Ben and Magdalena. Yup, I could get to liking those for our kid.”

“Don’t be absurd,” she snapped. That did it.

“You know, I think I will just go to hell and hit Jerry’s Bar for a drink. Because you’re driving me to drink, lady. But I’ll tell you one thing. No child of mine is going to wear an old person’s name!”

He stormed out of the trailer on his dad’s farm and headed into town on a gravel road he’d driven a thousand times. He came to a rolling stop where the road met the paved highway and whipped a right. He went a little wide, straddling the white lane marker when a kid from Gwinner came barreling down the road and hit him at eighty miles an hour.

Nettie never told anyone that the last words she said to her husband were in anger during an idiotic fight. She never admitted to anyone, not even her sisters, that if she hadn’t been so ridiculous that night in picking a fight, her Richard would never have been on that road and wouldn’t have ended up in a casket. She never admitted anything was wrong that night because to tell would admit that she had caused her husband’s death. She couldn’t bear for people to know that.

That stain was Nettie’s life secret. Her baby girl was born two months later, drawing her out of grief enough to be present and function. She named the baby Amber Magdalena. She told everyone that was the name they’d decided together.

But there was no such reprieve now. Now that she’d lost both her husband and the baby they’d made. Now that there was nothing left for her. Nothing.

Her family worried she’d never come back from that ledge of agony. They’d have been sick to know Nettie didn’t want to.

As she looked at Amber in that pretty lavender casket, Nettie wished there were an embalming fluid for the living. Something to make everything look like it was alright. But there wasn’t. She was resolved that nothing would ever be alright again.

The “acceptance” stage of grief is often called “a gift not afforded to everyone.” Nettie was one of those left empty-handed.

Harley gave her a week off with pay from the hardware store after Amber’s death. Nettie wasn’t sure if she should be grateful or if she should despise him for thinking a week was enough. But she needed the paycheck and staying at home alone was unbearable, so she went back to work and pretended she was “recovering.”

She gained twenty pounds in the first month, because the only thing—the ONLY THING—that gave her any comfort was sugar. She’d stop at Alice’s Bakery on her way to work and buy a half-dozen donuts, claiming she was sharing with Harley and customers, but she’d secretly eat them all herself during the morning. At noon, she’d go to the corner bar for one of their hamburgers with fries and drink a couple Cokes. After she got off work at three p.m., she’d hit Alice’s again, hanging in the kitchen with a cup of coffee and cookies or a cupcake—Alice never kept track—and spend the only minutes of her day in anything resembling normalcy.

Nettie was two years behind Alice in high school and they’d had a casual friendship all these years. Nettie had always been most likely to hang with her sisters, but since Amber’s death, it was more painful to be with a blood relative than with a girl you’d known most of your life who had other interests beyond your loss and grief.

To her sisters, Nettie explained, “I like Alice because she knows all the town gossip—she’s like her own newspaper, radio, and TV all in one!”

Alice Peters knew everything about everybody, because so many people passed through her delicious bakery every day. When you’re a willing listener in a bakery that always smells of sweet treats, and you have an endless coffeepot at the ready, people naturally hang out and talk.

Gossip in a small town is like currency. Alice not only had a full till, she loved to spend it.

“You know my secret?” Alice asked Nettie one day, stretching to entertain the sad woman. “I understand the difference in how men and women gossip.”

Nettie had never considered such a thing, but welcomed the relief of listening to a secret.

“Women gossip like a doubles game of ping-pong, everybody talking at once and throwing an idea back and forth. They’ll chew on a thing until it’s shredded, and then they move on. But men parcel out their thoughts slowly—two, three trains of thought hanging there with everyone naturally keeping track. Like multiple lanes of bowling where everyone knows each score. And in the middle of one train, somebody will tell a joke, and when they pick up again, nobody has to be reminded where they left off. So if you want gossip from women, they hand it over neat and tidy. But if you want it from men, you’ve got to hang in there for hours to get the whole story. I can eavesdrop with the best of them.”

Nettie laughed and Alice congratulated herself that she’d gotten the grieving woman to laugh for the first time in a long time.

It was no surprise that Nettie hung out at the bakery—everyone assumed it was for the sugar, and that’s where it started, but she really was after the ever-growing gossip garden. Some days the harvest was abundant. Some days it was just weeds. But it was always something and when you’re hopeless and bereft, you hang on to anything.

Besides, Alice often needed help decorating cookies or frosting cupcakes, and Nettie offered her services. It was a few more dollars and she had nothing else to do, anyway. Alice always tried to get out of the bakery by six p.m.—she had to be back at four-thirty a.m. to get the bread in her Reed Oven—and sometimes she and Nettie would run out to Dakota Magic Casino for supper. Other nights, Nettie would go home alone. The trailer was long gone and she’d inherited the farmhouse when Richard’s folks died. She’d either defrost a pizza or grab a bag of chips and pour some Black Velvet over ice.

The next mindless, meaningless day would start at six a.m. and she’d go through the motions all over again.

Except on Wednesdays. Wednesdays she only worked half days and she never stoppe

d at Alice’s. On Wednesdays, she picked up her standing order at Leona’s flower shop and took the two pink roses to Amber’s grave.

Nettie would lie on the ground next to her daughter’s headstone, even when there was snow, and talk to the girl who could never talk back.

This was the only place she ever felt any comfort. “Strange,” she once said to herself, “you’d think this was the last place I’d want to be. But this is where Amber is. And I have so much to tell her. All those things I never said. All those things she needs to know.”

Anyone overhearing her conversation would have been able to walk into a courtroom, put a hand on the Bible, and swear Nettie Schlener was nuts.

Nettie spoke to the grave as though she and Amber were sitting around the kitchen table having supper. She told the headstone the news in town and how the girls’ basketball team was doing. She told about beloved Aunt Gertie and the reports weren’t very good; the lady was failing fast. She’d hit a parked car last week and the family took away her keys. Poor thing cried all day. Nettie told about strange customers at the hardware and how Alice’s new cake recipe tasted. She even gave updates on Johnny.

“He’s still in a coma,” she’d report. “His mother is always with him. His father….well, you know his father. They don’t know if he’ll ever come out of it.”

There were regular news flashes on her cousins, aunts and uncles. “Your Uncle Dennis was so angry when you died,” Nettie told her. “I worried he might do something that would get him in trouble. But he’s calmed down. You know, they always do. Those men get so riled up and they’re like red hot pokers, but it doesn’t last. They say a woman holds a grudge a lot deeper than a man, and I think they’re right. Besides, Dennis has his kids to raise and they’re all active in sports and 4-H and his wife is into scrapbooking big-time, so she’s always going off to scrapbook conventions and leaving him to take care of everything at home. I’m betting sometimes he wishes he’d listened to Dad that Susie wasn’t the right woman for him.”

Nettie told her dead daughter that Maxine refused any of her clothes—even though Nettie was sure she and the other girls would want them. She ended up carting them to the Dakota Boy’s Ranch Thrift Shop in Fargo. “Remember how we liked shopping there?” After questions like that she’d pause, as though she expected an answer.

And then, in a voice just above a whisper, she’d tell Amber about Crabapple.

She’d end with her arms around the tombstone, kissing its cold surface.

Chapter Ten

Thanksgiving Day, 1999

Ralph Bonner’s World War II Marine picture hung in the hallway of his home in Northville, and Alice Peters never went down that hall without admiring her handsome uncle.

She smiled up at the picture and vowed that this was going to be a great Thanksgiving Day. And damned, if it wasn’t!

It was like recess. It was like half-time. It was a time-out.

It was a day when not one person mentioned Amber Schlener or Johnny Roth or Nettie Schlener. And certainly, nobody mentioned Crabapple.

“This is a day of thanksgiving, to be grateful for all we have,” Maggie Bonner announced as she sat her family around the dining room table, the kitchen table and the two card tables set up in the living room. Maggie and Ralph had a large home, but nobody had a home big enough to seat all the immediate relatives around one table.

Ralph had a brother and sister and their families—seven there.

Maggie had two sisters and a favorite niece with a large brood—eleven there.

Maggie and Ralph’s two boys and their families brought the total to twenty-six.

Thanksgiving was the only yearly holiday this blended clan shared together. All the others, the individual families had to juggle in-laws and out-laws. But Thanksgiving had been special since Ma and Pa Bonner demanded their kids come home for Thanksgiving, even after they got married.

This was the day that carried on the unofficial pastime of North Dakota—telling family stories. Joya Bonner always said she became a good reporter because she grew up listening to her elders and knew she was expected to accurately pass these stories on.

“How old were you, Ralph, when you first went to work?” Alice asked, knowing her mother would love to tell about the family’s regard for its firstborn.

“He was ten,” her mother jumped in. “He shoveled coal down at the railroad, and came home all dirty. He put every penny in Ma’s hands. And she needed it—Pa’s paycheck was never enough. When he was twelve, he bought me a new pair of shoes for school. I cried, I was so happy because all the other girls had new shoes and mine were patched. He was always showing up with sticks of peppermint candy, and you know, except for the peanut brittle Ma made, we never got candy. He was fifteen when he stood up to the old man who came home drunk and angry and we all were afraid of him. Ralph quit school at sixteen when Dad got him a job on the Great Northern. He gave half his pay to Ma. He’d give me a quarter every payday. And of course, he had to have some for himself. Man, he was a handsome kid. The girls just loved him. Didn’t they, Maggie?”

Everyone laughed and Ralph acted embarrassed by the attention. If his sister told that story once, she’d told it a hundred times, but she loved telling it and he secretly loved hearing it.

“I can’t believe you guys were afraid of Grandpa Bonner,” Alice offered, standing up for the man she and Joya had always adored, even if he did smell of snuff.

“Just a little,” Ralph jumped in, giving his siblings the eye that this was enough information.

“How come you never farmed?” Alice asked, and that led to the stories of how Great-Grandpa Bonner immigrated from Bruckenthal, Austria, and since he was a cobbler, they settled in town, and then Grandpa got a job on the railroad when he was just a boy…

Alice smiled to herself midway through the afternoon, as pumpkin, apple, and mince pie were offered. This is what life is supposed to be. Families carrying on traditions and telling stories and caring about one another in a town so safe, trikes are left on the driveway overnight and Harley’s Hardware keeps its Miracle Grow potting soil on the sidewalk.

Alice couldn’t imagine living anywhere else, especially not a big city with its awful, dirty problems that were broadcast every night on the evening news. What normally passed for crime in Northville were the few things Mrs. Jersey slipped into her purse at the drugstore. But every month, Mr. Jersey got a bill that he paid without a word, so that really didn’t count. You’d never see trash on the street or a traffic jam, even though there wasn’t a single traffic light.

Alice felt blessed to live in a town where nobody knew your address, but everyone knew where you lived.

“Tell me a story, Uncle Alph,” Danny demanded, as he climbed into his uncle’s lap and put his finger in Ralph’s pumpkin pie.

“It’s okay, it’s okay,” Ralph told the table as Danny’s father and mother both tried to shush him. Ralph had a special spot in his heart for his brother’s “slow” son, and they were in the storytelling mood anyway.

“Tell him the one about the poor John Wendle family,” Alice suggested, assuming her role as the town’s messenger.

“Danny wouldn’t like that one,” Ralph cautioned, and Alice saw the wisdom. You don’t tell a slow fourth-grader the story about a man who stands facing a blizzard and freezes to death saving his family. It would send the kid into hysterics.

Ralph had a better idea.

“Okay, Danny, want to hear how we deal with bad guys in Northville?”

Around the table, several sucked in their breath, fearing what was coming, but relieved when they heard it was the “Yegg” story.

“You weren’t even born yet—neither was your dad—when these bad men tried to rob the Northville State Bank back in ’29,” Ralph began. “You know what they called burglars back then—they called them ‘yeggs.’”

“Like eggs?”

Danny interrupted. Everyone laughed.

“Yes, like eggs. They got in through a back window and were trying to steal everything the bank had. You know, your grandpa had his money in that bank, and so did a lot of other people in town, and it would have been just terrible if they’d gotten away with it. But thankfully, one of the Barton boys was on his way home from his railroad job and he saw them. He ran home and woke up his four brothers and everyone grabbed a shotgun. Two of them watched the bank while the others ran to tell the bank president what was up. Well, while they waited—I’m not sure this was the smartest thing—the men watching the bank decided to shoot their shotguns to scare the robbers and alert the town. Those robbers came rushing out of that bank and shot back and the Barton boys reloaded and wounded two of them. They followed the blood and held those men until the sheriff arrived. The Fargo Forum even wrote a story about the whole thing. They said, ‘Local Boys Give Bandits Plenty of Number 6 Shot.’

“See Danny, in Northville, we take care of our families and we take care of business. We don’t let people rob us.”

The whole table was silent because they knew Ralph wasn’t talking about the yeggs anymore.

Chapter Eleven

Sunday, December 12, 1999

Johnny Roth came out of his coma on December 12th—about the time Crabapple was halfway home.

His mother was sitting next to him, holding his hand and talking to him like the nurses had suggested, just as she’d done since that first terrible night.

He was already in a coma when Lois and Paul Roth got the horrible call from the sheriff’s office in October, saying Johnny had been taken to the hospital in Breckenridge. They were offered no other news in that call, but you don’t get a call from the sheriff without knowing it has to be bad.

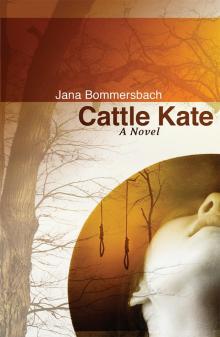

Cattle Kate

Cattle Kate Funeral Hotdish

Funeral Hotdish